Sunday Drive #13 – Gordon Murray – part 2.

McLaren – from Formula 1, to the automotive icon.

The previous edition of the Sunday Drive ended with Gordon Murray's departure from Brabham. The Brit had spent 17 years with the team based in Milton Keynes and earned significant recognition in the F1 paddock, which led to numerous offers (rumour has it even Maranello called). However, he ultimately decided to accept an offer from Woking, the home of McLaren.

Backstage Reorganization

Aside from the driver transfers that generated the most excitement in 1987, there were also a few changes among the engineering teams and engine suppliers. For McLaren, the 1984, 1985, and 1986 seasons were very successful: two constructors' championships and three drivers' titles. However, these years were far from idyllic. Following an unsuccessful season in 1985, Niki Lauda announced his retirement. He was replaced by Keke Rosberg, who also decided to end his career one year later. The second driver's seat for the 1987 season was taken by Stefan Johansson, but it was no secret that this was due to a failed attempt to bring Ayrton Senna to the team (he was contracted with Lotus until the end of 1987). In 1986, McLaren also ended its collaboration with John Barnard, an excellent engineer who found employment at Ferrari. McLaren's boss, Ron Dennis, needed a bold change in the technical department and brought in Gordon Murray.

Taking Control of Chaos

Murray agreed to join the team under several conditions: first, he wanted to become Technical Director, and second, his contract would last only three years. He began his career at McLaren by working on the car for the 1988 season – the MP4/4. He agreed with the team management that he would immediately get to work on the drawing board, which he still uses today, and begin designing a car that had to fit into the changing regulations. But before the car could be put on the track, the working environment of the Woking team had to be laid out.

In his memories from that time, Murray speaks with fascination about the surprise he felt at McLaren's chaotic organisation, despite its significantly larger budget compared to Brabham. The team, despite consisting of numerous designers and engineers, lacked clear structure and procedures for testing the durability of car components. Murray grouped the people together and imposed a regime.

MP4/4

The biggest controversy surrounding the most iconic car in Formula 1 history is the debate over who really designed the McLaren MP4/4.

With a new Honda V6 Turbo engine, the McLaren MP4/4 received several innovations. On the one hand, Gordon Murray, the team's Technical Director, claims credit for these, while on the other, Steve Nichols, the car's chief designer and Murray's protégé, also stakes a claim.

This media dispute is personal, as the two men did not get along. The answer to the question of how many fathers a success has, and how many a failure, is one we are all familiar with. Ideas such as the more reclined driver position, the engine placed as low as possible, and the three-shaft gearbox (instead of two shafts) transmitting power from a low-mounted clutch to the driveshaft, belong to Gordon Murray, as confirmed by some of McLaren's own engineers and Osamu Goto, head of development at Honda Racing. Steve Nichols' role is undisputed; he did a tremendous amount of work preparing the car in a very short time, but discrediting Murray's role is at least improper.

However, let's not forget one thing: the car would have meant nothing without the phenomenal performance of the two drivers, Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost. If not for Senna's collision at Imola, McLaren would have won every race in 1988.

F1 – Racing Technology on the Road

One evening, while waiting for a delayed flight at Linate Airport in Milan, Gordon Murray, Creighton Brown, Ron Dennis, and Mansour Akram Ojjeh (the last two were McLaren's owners) started chatting about the company's further development. The vision extended far beyond the racing arenas; the ambition was to create a road car. For Murray, this was an opportunity to find a new professional goal because, as he said himself, after twenty years in Formula 1, he had had enough. In 1988, work began on McLaren's first supercar, intended to dethrone the most significant designs of the time: the Ferrari F40, Porsche 959, Jaguar XJ220, and Bugatti EB110.

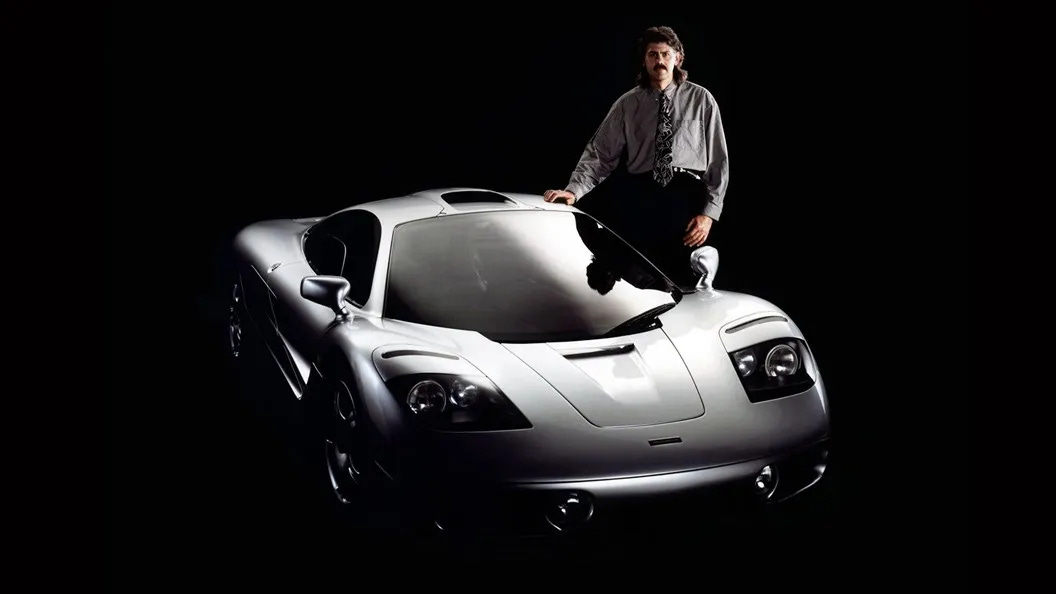

On 28th May 1992, the McLaren F1 XP1 prototype was unveiled in Monaco.

The prototype had mirrors mounted at the top of the A-pillar, with integrated indicators (possibly for the first time in history) but lacked any at the front of the body. Unfortunately, this solution did not receive homologation, and the production version had more conventional solutions. One of the first customers, fashion designer Ralph Lauren, had the mirrors installed in his car as per the prototype.

Delivers of the F1 to the customers began in 1994. Supersport machine was, in many ways, a pioneer. It was the first road car to cost 1 million dollars, the first with ground effect technology and active aerodynamics, and the first with a carbon fibre body structure. And, of course, the most distinctive feature: the central driver's seat with two side-passenger seats positioned behind it. For McLaren to be allowed on British roads, a change had to be made in road law, which until then only permitted cars with right-hand drive.

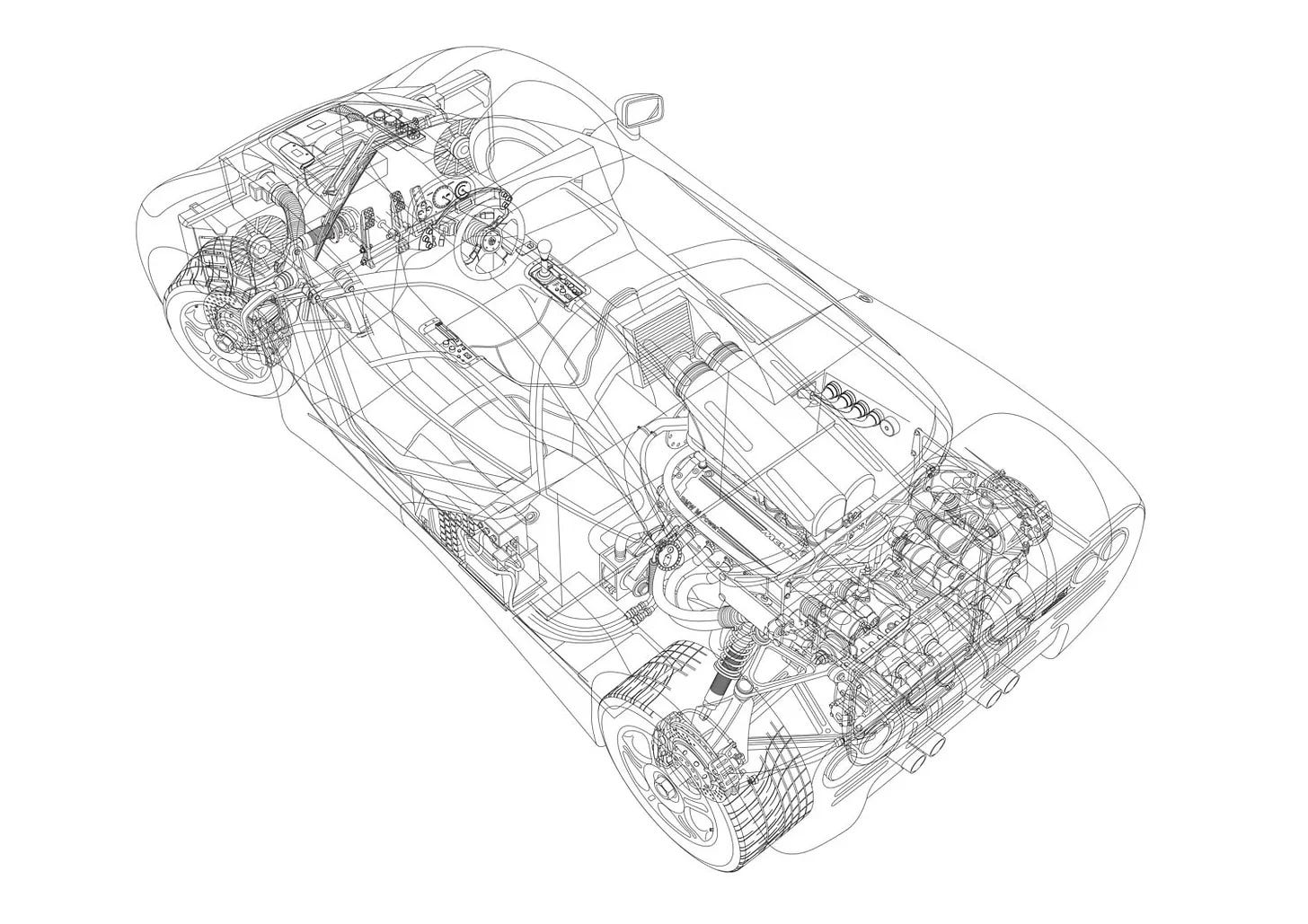

Even before the car took its final shape, there was an intense search for a power unit. Murray felt that it had to be at least a V10, preferably a V12. Talks began with Honda, who were supplying engines for McLaren's Formula 1 cars, but the marketing team announced that the 4.5-litre engine McLaren requested was not the type of technology the company wanted to be associated with. For a moment, Murray considered approaching Isuzu, who had presented a supercar prototype with a V12 under the hood, but talks went to dead end.

Murray pulled out a business card from his Brabham days and called his good friend at BMW, Paul Roche, a brilliant engine designer for the Bavarian Motorsport division. The design requirements: V10 or V12, no longer than 600 mm, weighing no more than 250 kg with accessories, and producing no less than 550 hp. The designer missed the weight target by 16 kg, but the power output exceeded expectations by 77 hp, much to everyone's delight.

Thus, a legend was born, breaking the speed record for production cars – 386 km/h, lond after surpassed by the Bugatti Veyron, but still unbeaten among naturally aspirated cars.

Racing Ban

In 1994, the BPR Global GT Series was founded as the successor to the World Supercar Championship. Several manufacturers, led by Porsche and Ferrari, expressed interest in participating. Private team owners, searching for cars on the open market, immediately turned to McLaren. However, Murray strongly opposed any involvement in racing. One of the interested buyers was Ray Bellm, who threatened Ron Dennis that if McLaren did not prepare a race-ready car for him, he would modify the road version himself. To avoid losing control over the car's construction and, more broadly, the brand's reputation, the team, including Murray, agreed to build one car. They removed unnecessary features from the interior (such as air conditioning and radio), limited the engine's power to 600 hp, improved the brakes, added radiators and a spoiler, and declared the car race-ready. The engine and gearbox remained unchanged. After a few race wins, McLaren decided to build another car and compete at Le Mans. Behind the wheel of car number 59, entered by Kokusai Kaihatsu Racing, were JJ Lehto (Finland), Yannick Dalmas (France), and Masanori Sekiya (Japan). After a race full of twists and turns, and having made the fewest mistakes, they won. In that edition, McLarens finished 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 13th.

The Ugly Duckling

McLaren's partnership with Mercedes began in 1995 with the supply of engines for their Formula 1 cars. The partnership grew stronger, and by 2000, Mercedes had purchased 40% of shares from Ron Dennis and Mansour Ojjeh. The offspring of this union was the 2003 Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren – the first composite car from Stuttgart. Gordon and his team were responsible for the technical aspects: construction, aerodynamics, and homologation. Additionally, McLaren built a factory and produced all the SLRs.

The challenge, however, lay in production volume. McLaren had previously produced around 30 units of the F1 per year, while Mercedes wanted to build 500 SLRs annually. This required the development of new methods for forming carbon fibre panels and bonding body components. Murray speaks fondly of the engineering behind the car, though he doesn’t like the looks, but had no influence over the design.

Despite its imperfections – particularly the bulky interior borrowed from the C-Class – the SLR has become an icon of the automotive world. It featured a remarkable engine and distinctive special editions, such as the Mercedes SLR McLaren Stirling Moss Edition, which paid tribute to the original 300 SLR and one of the most significant drivers in history, who won the Mille Miglia in 1955.

Next Week: Part Three

Thank you for your continued interest, and I invite you to subscribe to the newsletter. I also encourage you to support the site on Buy Me a Coffee orPatreon. The funds collected will be used to develop the Heel and Toe magazine and ultimately allow full focus on the project. In the aforementioned service, sales of photos of the tested cars, including from this article, have started. These are collector's prints in numbered series on archival papers.

Have a good one!