Happy Birthday!

I try not to use overly pompous words carelessly, but Gordon Murray IS A GENIUS. Last week, I realised that he celebrated his 78th birthday on the 18th of June. Therefore, I will dedicate this edition of the Sunday Drive to some of his Formula 1 car designs, and the next one to his road cars.

The South African Phenomenon

Gordon. Murray was born in Durban, the third-largest city in South Africa. He comes from a family of Scottish immigrants, and his father was involved in motorcycles, first racing them and then preparing them for races. Young Gordon was steeped in petrol from a young age and decided to become a racing driver as a teenager. Alongside starting his studies at the Durban University of Technology, he began working on his race car. The principles were simple and are the foundations of Murray's contemporary creations: the lowest possible weight (the first car weighed around 400 kg) and a low centre of gravity. On top of that, it had the appearance known from contemporary Lotuses: an open body and exposed front wheels. The 1.1-litre engine came from a Ford Anglia and, after modifications, achieved 90 brake horsepower. Thus, the IGM Ford Special was born, which the young driver raced for two seasons in the National Sports Car Championship, winning several races.

The status of the original car is unknown, but in 2017 Gordon drove to the top of the hill at Goodwood in a replica of the IGM Ford Special.

Brabham

In 1969, many things happened: the hippie movement reached its peak at the Woodstock festival, Pele scored his thousandth goal, Neil Armstrong landed on the moon (allegedly), and Gordon Murray packed his bags and sailed on a cargo ship to the United Kingdom. He had an ambitious plan: he wanted to join Lotus, and after previously exchanging correspondence with Mr Colin Chapman, he was almost certain of a position as an engineer. During the voyage from South Africa, an economic storm hit the United Kingdom, and the doors to the Hethel manufacturer closed in young Gordon's face. Brabham showed interest in working with him, where Gordon began designing and coming up with technical innovations. Bernie Ecclestone, who bought the team in 1972, quickly realised Murray's potential and soon appointed him as the chief designer. Our hero was then 26 years old.

Yet, after several team successes with Brabham during that period, Colin Chapman offered Murray a position with the Lotus racing team. However, Murray declined for two reasons: first and foremost, Bernie Ecclestone gave him complete design freedom, which he probably wouldn't have had under Chapman's leadership, and secondly, he feared a clash of two autocratic and disagreeable characters (his and Chapman's).

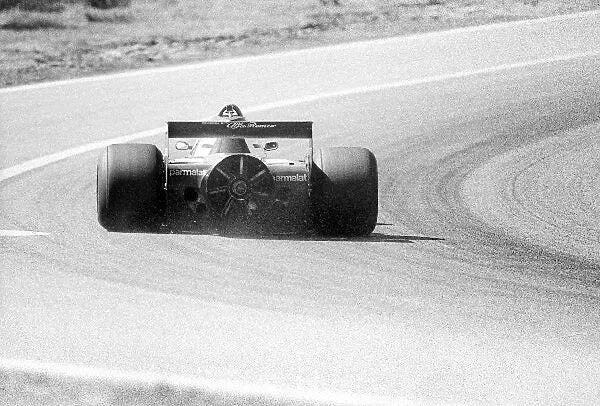

BT46B – Fan Car

The 1978 Formula 1 season was dominated by cars using ground effect, which Lotus had most effectively adopted in the model 78, with Mario Andretti on board – winning the championship. Colin Chapman's Black Beauty had a floor resembling an inverted aircraft wing and utilised the same ground effect, except instead of lifting the structure, it sucked it to the track. Brabham, aspiring to victories, presented the BT46 model, but neither Niki Lauda nor John Watson could challenge Andretti. Until the Swedish Grand Prix...

Exactly halfway through the season, the team unveiled the “B” variant of their car. The innovation that Murray worked on was a fan that pumped air out from under the car. Since the fan was engine-driven, it generated downforce regardless of the car's speed. Moreover, calculations strongly suggested that a car with the engine running at 12000RPM could be effectively suctioned to the ceiling! The biggest challenge for the engineers was explaining to the drivers how to approach aerodynamics in the context of their old habits. Murray recalls that Niki Lauda understood it the fastest, with a cornering advantage of up to 50km/h!

Reaching such speeds naturally involves some risks. Firstly, the tyres of that time were not designed for such loads. The Fan Car had to run with higher pressure, and talks with manufacturers about a new design with reinforced sidewalls were just beginning. Another problem was the sealing of the bottom of the vehicle. To maintain proper vacuum, the skirts fixed in the underbody couldn't be damaged. Murray came up with the idea of measuring the pressure under the floor and used a solution from aviation – specially adapted altimeters measuring static pressure differences. The drivers had gauges in the cockpit that they had to monitor; if the pressure dropped (due to broken skirts), they would lose grip, and at such speeds in the corners, they could simplu take off.

The first tests on the Anderstorp track astonished the competitors. False rumours about stones flying out of the fan began circulating around the paddock, but Gordon Murray quickly dealt with the bad PR, explaining to the competitors how physics works (stones, if they were to fly out through the fan, would fly sideways). Before the race, the car was inspected – sealed (including the transporter) and subjected to a thorough examination. After confirming no irregularities, the car was allowed to compete in the remaining races of the season. Niki Lauda won the race, describing the performance difference between him and the competitors as “humiliating.” Unfortunately, politics took over, and rebellious constructors threatened Bernie Ecclestone with leaving the newly formed FOCA (Formula One Constructors Association). Due to his far-reaching plans, he decided to withdraw the BT46B from racing and return to a more conservative car design – the BT46C variant.

End of an Era

Five years later, ground effect was banned by the FIA. The announcement came six weeks before the start of the 1983 season and put the teams in a difficult position, as they had to start from scratch with flat-bottomed cars. Preparing the Brabham BT52, Gordon Murray took a radical approach and shifted the weight distribution to the rear (70%) to improve traction. The cockpit shape resembled a fighter jet cabin with attached wheels and spoilers.

Murray's vision for that season was more holistic, and many innovations were developed around the car to gain maximum time advantage over competitors. In those days, cars started with enough fuel for the entire race and on one set of tyres. The BT52 was the first to regularly use strategic pit stops, allowing it to have less fuel and a lower starting weight (one pound of car weight translated to half a second per lap) and fresh tyres.

Here is the first strategic pit stop in history by Nelson Piquet and the Brabham team.

To shorten pit stop times, the car was equipped with pneumatic jacks powered by an external compressor, and for the first time in Formula 1, air guns were used to unscrew the wheel lug nuts. Instead of electric heating blankets, the tyres were heated in a large gas boiler. The fuel was pumped with such energy that over 100 litres entered the BT52's tank in just three seconds!

The end of a Fairy Tale

The origins of the team bearing the name of its founder, Jack Brabham, date back to 1960. The team made its first Formula 1 start in 1962. Before Bernie Ecclestone and Gordon Murray joined, Jack Brabham and his drivers had won dozens of races and two titles. Ecclestone's acquisition of the team was not an attempt to revive a dead horse but an investment that, along with his cunning, began to yield increasing influence in the legal, media, and lobbying heart of F1. The enthusiasm for running the team waned in the mid-eighties, also due to poor results from drivers and engineers. The car prepared for the 1986 season was once again full of technical innovations by Gordon Murray. The main goal was to drastically lower the centre of gravity, and the most noticeable (for the drivers' backs) change was a more aggressive seat recline angle. Instead of 45 degrees, it was proposed to be 30. Other changes included tilting the engine by 18 degrees and using a new seven-speed gearbox.

New sponsorship contracts with Olivetti and Pirelli not only provided cash flow, but also required the hiring of Italian drivers. The team included Elio De Angelis and Riccardo Patrese. The car turned out to be a failure. Constant gearbox problems and an overheating engine added fuel to the fire of frustration.

The team's core broke on the 15th of May 1986, when Elio De Angelis died in an accident during tests at the Paul Ricard circuit. Mourning, chaos, and mutual accusations prompted Gordon Murray to leave for McLaren…

But more on that next week.

Thank you for your continued interest, and I invite you to subscribe to the newsletter. I also encourage you to support the site on Buy Me a Coffee or Patreon. The funds collected will be used to develop the Heel and Toe magazine and ultimately allow full focus on the project. In the aforementioned service, sales of photos of the tested cars, including from this article, have started. These are collector's prints in numbered series on archival papers.

Have a good one!